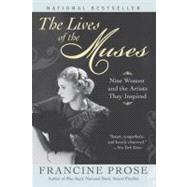

The Lives of the Muses

by Prose, FrancineBuy New

Rent Book

Rent Digital

Used Book

We're Sorry

Sold Out

How Marketplace Works:

- This item is offered by an independent seller and not shipped from our warehouse

- Item details like edition and cover design may differ from our description; see seller's comments before ordering.

- Sellers much confirm and ship within two business days; otherwise, the order will be cancelled and refunded.

- Marketplace purchases cannot be returned to eCampus.com. Contact the seller directly for inquiries; if no response within two days, contact customer service.

- Additional shipping costs apply to Marketplace purchases. Review shipping costs at checkout.

Summary

Excerpts

Nine Women & the Artists They Inspired

Chapter One

Hester Thrale

On a spring morning in 1766, Henry and Hester Thrale visited Dr. Samuel Johnson in his rooms at Johnson's Court.

The lively, attractive young couple had known the famous writer since 1764, when the playwright Arthur Murphy had brought Johnson to dinner at the Thrales' estate in Streatham Park, a few miles from central London. Since then, he had been a regular guest at Streatham, and at the Thrales' city place in Southwark, on the grounds of their profitable brewery. But lately, Johnson's visits had tapered off, and the Thrales had reason to suspect that he was suffering from one of the profound and terrifying fits of melancholia that had plagued him for most of his fifty-seven years. Already, they had grown close enough for Johnson to have confided his fears about "the horrible condition of his mind, which he said was nearly distracted."

Unlikely on the surface, the friendship was a tremendous coup for the socially ambitious Thrales. Johnson was famous not only for having written the Dictionary, the Rambler essays, The Life of Savage, and Rasselas but for his witty conversation. Among fashionable Londoners, watching the doctor talk had become a sort of spectator sport; at parties, guests crowded, four and five deep, around his chair to listen.

Johnson brought his own celebrity talking-and-sparring partners—David Garrick, Oliver Goldsmith, Sir Joshua Reynolds—along with him to Streatham, possibly because brisk repartee was not his host's strong suit. Well meaning and personable, properly insistent on his masculine right to overeat, hunt, and cheat publicly on his wife, Henry Thrale lacked, according to Johnson, the finer social skills. "His conversation does not show the minute hand; but he strikes the hour very correctly." He was the sort of rich, dull, solid fellow—"such dead, though excellent, mutton," to quote Virginia Woolf's wicked assessment of Rebecca West's husband—who turns up, with surprising frequency, in the lives of the muses.

Johnson liked the wealthy brewer; he admired the manly way he ran his household, and enjoyed the benefits of his expensive tastes in food and wine. Driven by an increasing horror of solitude and a craving for human companionship, the writer was drawn to the vibrant domesticity of Streatham, and especially to his hostess, a slight, dark-eyed Welsh fireball, who was disputatious, flirtatious, quick, well educated, and (unlike many of their contemporaries) unafraid of a man whom she described as having "a roughness in his manner which subdued the saucy and terrified the meek; this was, when I knew him, the prominent part of a character which few durst venture to approach so nearly."

Chroniclers of the period record the sparkling sorties that flew back and forth across the table between Samuel Johnson and Mrs. Thrale. And her own Anecdotes of the Late Samuel Johnson, LL.D., published in 1785, functions as a compendium not only of the writer's witticisms, but also of their exchanges on subjects ranging from faith to incredulity, from ghostly apparitions to the value of everyday knowledge, from marital discord to convent life, from the pleasures of traveling by coach to the rewards of reading Don Quixote, from the correct way to raise children to the necessity of constantly measuring one's minor complaints against the greater sufferings and privations of the poor.

The Thrales were tolerant of the writer's notorious eccentricities. Eventually, they would assign a servant to stand outside his door with a fresh wig for him to wear to dinner, since he so often singed the front of his wig by reading too close to the lamp. Nearly blind, disfigured by pockmarks, Johnson suffered from scrofula and a host of somatic complaints, as well as an array of psychological symptoms that, today, would virtually ensure that he was medicated for Tourette's, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, to name just the obvious syndromes. (The ongoing discussion of Johnson's "case" in medical literature has made him one of those figures, like Van Gogh and Lizzie Siddal, whose health care improved dramatically after death.) Happily, Samuel Johnson's own more permissive era was sufficiently enchanted by his intelligence, humor, and unflagging energy to overlook his rocking from foot to foot, mumbling, twitching, emitting startling verbal outbursts, obsessively counting his footsteps, touching each lamppost in the street, and performing an elaborate shuffle before he could enter a doorway.

The Thrales were used to the doctor's tics. Yet nothing could have prepared them for the scene they found on that May morning when at last they were admitted to the writer's rooms at Johnson's Court. His friend John Delap was just leaving, and it must have been instantly obvious—from how pathetically he begged Delap to include him in his prayers—that the great Samuel Johnson was veering out of control.

Left alone with the Thrales, Johnson became so overwrought, so violent in his self-accusations, so reckless in alluding to the sins for which he said he needed forgiveness that Henry and Hester were soon caught up in the general hysteria. "I felt excessively affected with grief, and well remember my husband involuntarily lifted up one hand to shut his mouth, from provocation at hearing a man so wildly proclaim what he could at last persuade no one to believe; and what, if true, would have been so very unfit to reveal."

It was an extraordinary scene: the handsome brewer clapping one hand over the mouth of London's most celebrated literary figure, while his agitated wife looked on in dread and horror. Something irreversible was happening to their friendship! The balance of power and need was being tipped forever by what Johnson was letting them see. They'd arrived as friends and hosts flattered by the doctor's affections, but uninvited, and perhaps a bit uncertain about their welcome and the future of their friendship. And now they had been drawn into this theatrical, eroticized tableau, from which they would emerge as guardians, saviors, confessors . . .

The Lives of the MusesNine Women & the Artists They Inspired. Copyright © by Francine Prose. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. Available now wherever books are sold.

Excerpted from Lives of the Muses: Nine Women and the Artists They Inspired by Francine Prose

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.

An electronic version of this book is available through VitalSource.

This book is viewable on PC, Mac, iPhone, iPad, iPod Touch, and most smartphones.

By purchasing, you will be able to view this book online, as well as download it, for the chosen number of days.

Digital License

You are licensing a digital product for a set duration. Durations are set forth in the product description, with "Lifetime" typically meaning five (5) years of online access and permanent download to a supported device. All licenses are non-transferable.

More details can be found here.

A downloadable version of this book is available through the eCampus Reader or compatible Adobe readers.

Applications are available on iOS, Android, PC, Mac, and Windows Mobile platforms.

Please view the compatibility matrix prior to purchase.